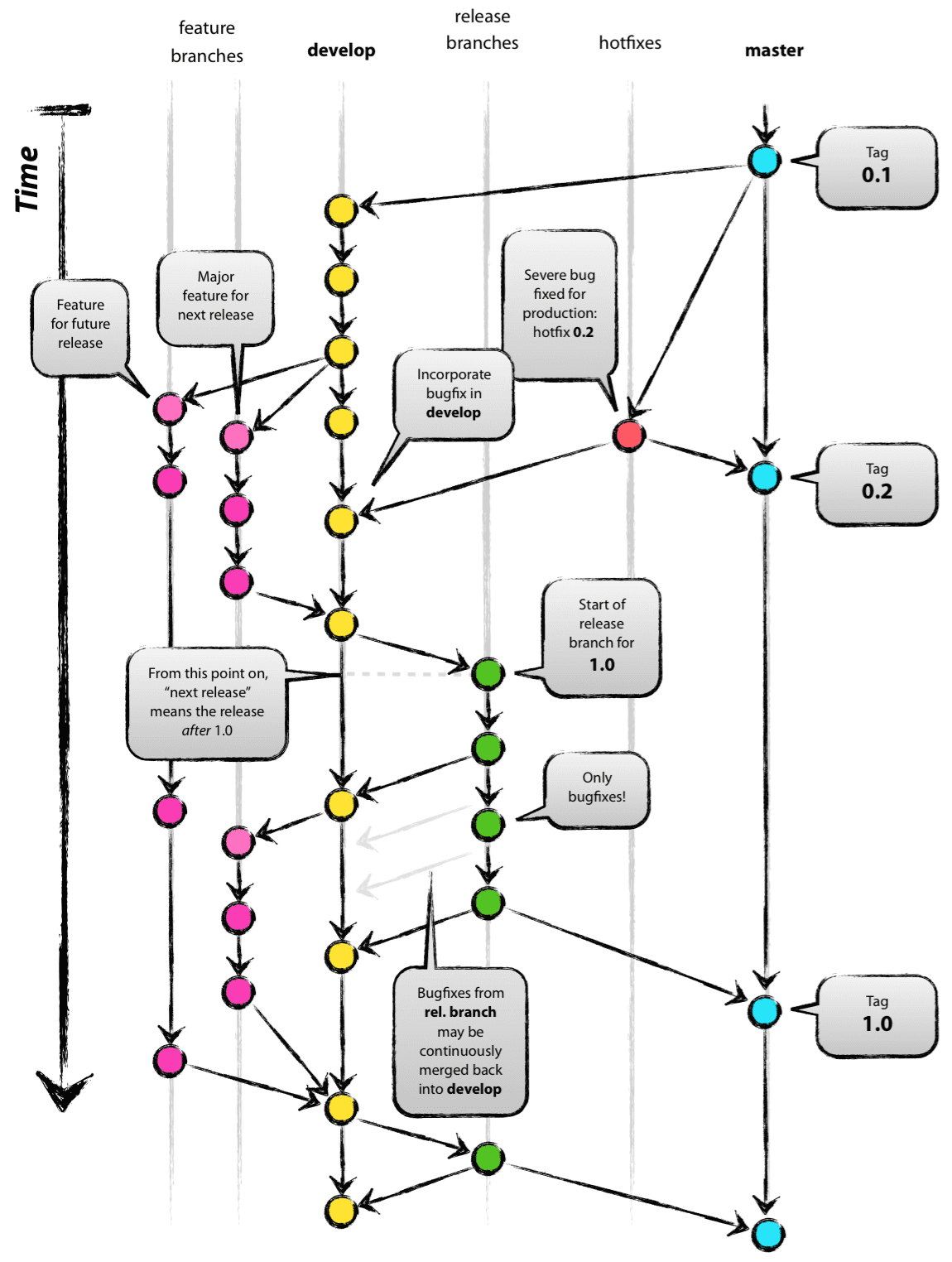

About 10 years ago, Vincent Driessen published the seminal post “A successful Git branching model” describing a logical process for developing, releasing, and fixing software projects using Git branches. It quickly became knows as Gitflow, and is one of the most widely used branching models for release-based software development.

The essential branches in the Gitflow branching model

Gitflow was perhaps the first well-publicized Git branching model. Other branching models followed, the most famous being GitHub Flow, which proposed a more simplified philosophy aimed at software deployed to production continuously.

Software development vs. exploratory research

Unlike software development, research is not composed of a set of known features in various states of development. Research is exploratory and open-ended: presented with a question, we attempt to answer it, often using multiple hypotheses that we accept, reject, or evolve as new information is discovered.

This requires that we adapt Git branching models to the research process. For example, many branches of exploration might never be incorporated into our published work, but are nevertheless valuable as chronicled paths: helping us answer questions like: “what would have happened if we had done X,Y,Z?”, the oft-asked “did we ever try A,B, or C?”, and the occasional “oops, we tried A, B, and C but we just discovered a bug and need to re-try A and B with the bug fixed”.

“many branches of exploration might never be incorporated into our published work, but are nevertheless valuable as chronicled paths”

In this post, in the spirit of Gitflow and GitHub Flow, we outline a branching model used to successfully manage research and development projects for the past few years. In this manifestation, Git is the modern, collaborative “lab-notebook” that allows an individual or group to chronicle:

- what hypotheses do we want to explore at each juncture?

- what results do a particular hypothesis produce?

- what hypotheses were studied, or not, to produce a particular set of results?

This is reproducibility not only in the sense that a set of results is reproducible given the current code, but the entire research process is reproducible.

In what follows, we propose Research Flow, a hybrid Git branching model adapted for research, and we end with a few handy Git and GitHub tips and patterns that facilitate reproducibilty, collaboration, and communication.

In case you’re asking, ‘Why git?’

This article assumes the reader understands the fundamental value of version control and has already chosen to use git. It assumes intermediate knowledge of Git and GitHub. For those getting started with Git, some recommended starter resources follow:

- Jenny Bryan’s Happy Git and GitHub for the useR

- Bryan J. 2017. Excuse me, do you have a moment to talk about version control? PeerJ Preprints 5:e3159v2 https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.3159v2

- Visualizing Git

Adapting Git workflows for research

The original “A successful Git branching model” article defines a set of branches (master, develop, feature, release, hotfix) with specific rules as to how they are created and merged. Similarly, GitHub Flow defines just two types of branches (master, any other branch).

Research Flow

We propose a hybrid workflow for research with the following modifications:

- two principal branches

- master

- devel

- GitHub releases are used for publication:

- master chronicles the publication of results

- devel contains work-in-progress

- to publish, devel is merged into master and a release is created

- we adapt the semantic versioning of software releases to publication (see below)

- we use research branches to sandbox exploratory work

- these are just GitHub Flow’s familiar any other branches: descriptively-named branches containing any proposed changes

Features of Research Flow

Using this, any visitor to a Research Flow repo can:

- browse the most recently published results by visiting the master branch

- check-out a previous publication via its tag, eg.

git checkout v1.1.0 (2019-10-15) - view available publications, and see how they have evolved, by visiting the repo’s releases page

- peek at work-in-progress in the devel branch

- contribute to work-in-progress by creating a descriptively-named research branch, adding their updates, and submitting a pull request to merge into devel or another research branch

Research Flow details

Releases on master are now publications

In release-based software development, software features are developed and incorporated into a particular release. In the research process, we publish what we believe to be the truth periodically via publications (think journal article, a group presentation, or even an email).

In Research Flow:

- master holds a record of tagged releases that represent publications

- cloning the repo or visiting its default main branch (master) allows one to browse the most recent publication

- visiting the repo’s releases page shows what publications exist

- comparing releases allows one to see see how publications have changed.

Semantic versioning applied to publication

In release-based software development, releases are commonly labeled with a semantic version that defines how the software functionality has changed from the previous release.

In our research-flow context, master holds a record of published works, semantically versioned to show how the published information has changed.

To help quickly understand how publications have changed, we recommend versioning publications with Major.Minor.Patch (eg. 1.0.0), followed by an optional publication date:

Major: tracks changes to already published information including information removalMinor: tracks new information added that doesn’t conflict with already published informationPatch: tracks adjustments to how information that has already been published is presented, no substantial changes to the information itself

An example of a sequence of publication release tags on master:

v1.0.0 (2019-10-01) # first publication with result A (first publication, major)

v1.1.0 (2019-10-15) # added code and new results B, C (minor)

v1.1.1 (2019-10-16) # fixed typo, added graph showing C more clearly (patch)

v2.0.0 (2019-11-30) # removed result A based on now invalidated data (major)

v3.0.0 (2019-12-05) # fixed bug in calculation of B, meaning the B result has changed, reformatted graph (major overrides patch)Research branches

Research branches are just normal branches that can be compared to other research branches or the development branch. They can be created by branching off of devel or another research branch.

Research branch examples

Exploring alternatives

Imagine a set of processes {A, B, C} that takes some data input I1 and produces some output O1. The question arises, “say we skip the cumbersome B and C steps and modify A to use I1 and I2, could we produce an O2 that is the same as O1 in all cases?”.

You would like to test this alternative, but don’t want to modify the existing code, nor the O1 results. Further, you want to be able to create 01 values for a range of parameters and compare the O2 results for those same parameters.

The solution? Create a research branch, implement the changes, and compare O2 to O1. If this refactoring is favorable, merge the research branch into devel. If not, then don’t merge it, but do log what was done and why it was considered unsuccessful. If you need to come back to the branch later, it will be there: unmerged branches are still valuable.

Collaborating in a repo

Imagine researchers A and B collaborating on the same repo. Their work can be logged in their respective forks or branches, ie. A/optimizer and B/simplify-test, before deciding to merge them into devel for publication, or not. If A/optimizer doesn’t produce valuable results, it may be orphaned, but logged in the repo for posterity.

Frequently asked questions

Isn’t this overkill? We usually only publish one thing and then make small adjustments before starting a new project.

Many research projects might never need to use more than a master and develop branch. They might only publish once and not need any semantic understanding of what was changed between publications. They might even just start out committing everything to master. That’s fine. The purpose of Research Flow is to make it easier to understand and manage different branches of research when things get more complex.

Perhaps the simplest answer:

If Research Flow isn’t solving a problem you feel like you have run into before, don’t use it

When should we create a research branch?

Possibly the most obvious reason to create a research branch:

you or a collaborator want to significantly alter an existing branch but also want to easily be able to “go back to how it was”

Why not just do everything on devel or create separate files or functions to explore different research ideas?

This does work in simple scenarios, however when projects get complicated and involve multi-file, multi-function, or multi-researcher processes, keeping track of dependencies becomes challenging. Undo’ing and redo’ing changes does too. Separating work into research branches isolates processes until the team decides what should be incorporated into published results.

Can I publish two articles from the same repo?

Remember, we are not just publishing an article, we’re publishing the entire devel branch, articles and code included. Therefore, the publication’s version needs to consider the state of the repo, not a particular article. If a second article is produced, it would resemble a new file in the repo. This represents new information to be shared, hence at least an increase of the minor version in a subsequent publication. The articles themselves may need their own version histories or supporting documentation via something like a CHANGES.md file.

What about persistent data across multiple branches?

When using multiple branches, special care must be taken to handle and separate branch-specific data, ie. the rsch/1 branch should not be overwriting data that the rsch/2 branch might access. This can be done fairly easily, but it is crucial that it is done.

Handy patterns and tips

The GitHub permalink

As progress is made in any branch, one can link to a specific line of code in an R script using GitHub permalinks.

Imagine you have published your results to master. You present your results and share a presentation that includes a link to the the R/results.R script file on your master branch so that a reader can reproduce the exact same graph. As long as you never change R/results.R, everything will work fine.

But now say you decide to reformat your graph extensively by changing the code in R/results.R. You do so and then publish again to master. The issue now is that the presentation you shared still references the same R/results.R file. When someone reading the presentation visits the link to R/results.R to reproduce your results, the graph be different. Fix this by sharing a permalink to the exact line of code that produced the graph- this will never change, no matter how many times you publish to master.

Until recently, we avoided using RMarkdown files because they were rendered by GitHub as markdown and hence did not have permlink features. We are glad to report that this is no longer the case.

Archiving versioned copies of presentations

When presenting results, archive a version of the presentation aligned to the release on master. In other words, “Save a copy” of your presentation documents and label them with the master version that they refer to. In a google-doc, for example, the original cloud document might continue to evolve, but you can view the copy of the document (or even use google docs’ built-in versionin’s “name this version” functionality) that has the same version as the earlier publication. This is often useful when having to consider “what were we thinking when we presented this?”.

Branch histories in repo

Including a ## Branch history section in README.md, or branch_history.md will help you understand what the branch was attempting to address and what the results were. For example, suppose your branching looks like this (o represents a commit, and \ represents a branching action):

master o-------------------------

devel \--o--o--o---------------

rsch/1 \--o--o--o-----o-----

rsch/1b \ \--o--o--o-

rsch/2 \--o--o----------o-In other words, you were working on devel and then branched off rsch/1 and rsch/2 to work on two separate issues. You then added commits to devel, rsch/1, and rsch/2 before branching off from rsch/1 to rsch/1b.

Say you’re on a particular sub-branch, like rsch/1b: how do you know what issues you were attempting to address and what the results were?

A simple solution is to look at the commit history using git log, or even view the history in GitHub. However, when results are derived from the commits they may need to be summarized. Logging comments to a file allows you to remind your future self of what you were doing and what the results were.

In this case, on rsch/1b we might have something like:

## Branch history

Most recent parent branch first:

#rsch/1b

removed secondary dataset and verified we

produce the same results

# rsch/1

Branched from devel to modify all queries

for data provider 1 instead of 0

Branching rsch/1b to verify elimination of

secondary data set produces same results

# devel

Developing initial model with data provider 0

Branching to rsch/1 and rsch/2 to test model

on data providers 1 and 2

# master

first commit

Whereas on devel, we might have something like:

## Branch history

Most recent parent branch first:

# devel

Developing initial model with data provider 0

Branching to rsch/1 and rsch/2 to test model

on data providers 1 and 2

Added output metrics for model

# master

first commit

Additionally, when deciding to abandon a research branch, it is useful to log why things didn’t work out. We have found that we don’t often come back to abandoned branches, but when we do, it can save days of work.

Comparing branches

GitHub allows you to compare changes between branches through its pull request feature. To do this, push a branch to the repo (or to a fork of the repo) and then go to the repo’s main page. Click on “New pull request” next to the branch button and then choose the base: and compare: branch options to choose the two branches you want to compare. You don’t have to create the pull request, you can just view the differences between files. This is often helpful in understanding what changed between a research branch and the devel branch prior to merging the research branch modifications into devel. This functionality is also available on the Git command-line-interface via git diff.

Final words

Research Flow is not a Git/GitHub reproducible research panacea. On the other hand, Research Flow does provide a few simple rules to tailor Git usage to reproducible research, in a format that is hopefully permissive enough to be incorporated as-needed into existing workflows. It emphasizes the value of chronicling abandoned, un-merged branches and proposes norms for publication and development. If you do end up incorporating it into your work, I would be interested in hearing about it.